Some of the best Galleries & Museums in Manchester are here on Oxford Road Corridor. Explore a diverse programme for all cultural enthusiasts.

This route will guide you through the University of Manchester and NHS Foundation Trust campuses to Whitworth Park. On your way, you’ll tread in the footsteps of numerous Nobel prize winners, cross paths with cultural giants and enjoy some of Manchester’s most beautiful architecture.

University Green is a relatively new green space. It is part of a landscaping scheme undertaken by the universities in Manchester with the ambition to make themselves as attractive as possible. Along its north side, there are a range of shops and bars underneath the Alliance Manchester Business School. This has a complex history but is now considered one of the most prestigious of European business schools. Academic management trading goes back to 1918 in Manchester and the old Municipal School of Technology we encountered on Walk One of this series. The Business School is named after a prominent sponsor, the Iranian-born, Mancunian-raised industrialist and philanthropist Lord David Alliance. On the other side of University Green is the Arthur Lewis Building. Lewis (1915-1991) was the first black Nobel Prize winner in an academic category, in his case, for economics. He partly developed his ‘Lewis Model’ in Manchester which describes how development was an isolated exercise but one in which political, social and cultural influences were crucial.

A plaque on the wall of the building here declares this to be the building where Professor Williams and Kilburn in 1948 developed the first computer with an electronically stored program. They called this, aptly, ‘Baby’ and there is a replica in the Science and Industry Museum, Manchester. In Freddie Williams’ words: “A programme was laboriously inserted and the start switch pressed. Immediately the spots on the display tube entered a mad dance. In early trials it was a dance of death leading to no useful result, and what was even worse, without yielding any clue as to what was wrong. But one day it stopped, and there, shining brightly in the expected place, was the expected answer. It was a moment to remember. This was in June 1948, and nothing was ever the same again.”

This is a charming building full of picturesque views across halls and stairways, complete with internal bridges and quirky nooks and crannies housing one of the great provincial museum collections. The oldest elements are by Manchester Town Hall architect, Alfred Waterhouse, from 1888. It was extended by his son Paul in 1912 and 1927 and has undergone extensive refurbishment on several occasions.

Waterhouse was asked to produce a building in line with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, with a progression of galleries. Waterhouse in his Natural History Museum in London, opened in 1881, had been asked to produce a building in line with Richard Owen’s Creationist ideas. Architects need to be flexible to gain commissions.

Manchester Museum is particularly strong in natural sciences, geology and botany, including a vivarium with live beasts and archaeology including a well-known section on Ancient Egypt. The latest refurbishment includes a South Asian gallery.

This redbrick building once hosted one of the best ‘boy bands’ of physicists the world has ever known. Or maybe that should be a ‘nuclear family’, a very diverse nuclear family. The leader of the group was New Zealander Sir Ernest Rutherford who had already gained a Nobel prize in physics by the time he arrived in 1907. Others in his group would include Hans Geiger, the German creator of the eponymous radiation counter, Lawrence Bragg, an Australian and winner of the 1915 Nobel Prize for X-ray crystallography, Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian and analytic philosopher and mathematician and the great Niels Bohr, a Dane and the father of quantum physics. Together the team had many breakthroughs. In 1917 Rutherford discovered that he could ‘disintegrate the nuclei of nitrogen atoms by firing particles from a radioactive source which, in turn, resulted in the release of fast protons.’ He had effectively split the atom.

A little down from the Museum another archway opens from Oxford Road and leads into the University of Manchester’s Main Quadrangle the oldest part of the University on this site. Before entering under the arch, note in a niche on the left, a statue of John Owens. John Owens died in 1846 and left £96,654 for the founding of a non-denominational university.

Owens College opened in 1851 on Quay Street, a mile north, before it was decided to move to a larger site, this one, in 1869. In 1880 it became the first part of the Victoria University with other colleges in Liverpool and Leeds. By 1903 it became independent as the Victoria University of Manchester. In 2003 it merged with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology to become just the University of Manchester. It has 25 Nobel laureates to its credit.

Once in the quadrangle then straight ahead is the oldest part of the University of Manchester here from 1873/4. The style of all the buildings surrounding the quadrangle is neo-Gothic and most were designed by Alfred Waterhouse who we have encountered before. Many of the buildings, as with the museum, were finished off by his son Paul Waterhouse. The main quadrangle provides a grand space to stare at architecture.

The Whitworth Hall, at the south-eastern end of the complex, is a mighty space with a grand organ and a stunningly good hammer-beam ceiling. It is worth a visit. The organ was donated by Enriqueta Rylands, the first woman to be awarded the honour of freedom of the city. She was the philanthropist who provided John Rylands Library on Deansgate which is now managed by the University.

Set back from Oxford Road is Contact, a space which was set up by the University as Manchester’s Young People’s Theatre. The zany exterior is from Short & Associates in the later nineties. The two stacked ranks of chimney ventilators are part of a natural ventilation system. Many other elements play on the notion of theatrical forms with supporting struts shaped like theatrical spears and the main entrance taking the form of a stage curtain. The theatre was extended by Sheppard Robson in 2022 to complement the 1990s work.

On the left-hand side, eastern, of Oxford Road is the former Royal Eye Hospital from 1886 in fierce red brick with terracotta panels of Christ healing the blind. This is now CityLabs, a pioneering research centre for health innovation. The next building on the same side has a long façade with pavilions at the entrance. This was built as Manchester Royal Infirmary and dates from 1908 designed by ET Hall. If it looks like it could be in Greenwich then that is because it is in the same Baroque style. Hall also designed the Liberty & Co department store in London.

This is one of the great galleries of Manchester, but where does the name come from?

There are many occasions Sir Joseph Whitworth’s name has been referenced on these Oxford Road Corridor tours. Whitworth (1803-1887) has been called the father of precision engineering: he was a colossus in his field.

One of his inventions helps the most humble of amateur engineers change a plug. It was Whitworth who came up with the universal screw gauge with the result that people can fix each other’s machines, or change any plug anywhere, without applying back to the original manufacturer of the machine or plug for supplies of their particular screw gauge.

Whitworth was also incredibly philanthropic and it was his legacy funds that provided for the Whitworth Art Gallery, Whitworth Hall and public land on Whitworth Street, see Walk One of this series. The gallery was founded in 1885 but the main, rather heavy façade dates from 1908 by JW Beaumont. The second phase lies inside and is from 1963-8. It is a light and airy design from Bikerdike which is a joy and a triumph of the period. This was enhanced and extended in 2015 by MUMA architects and is another success. The collection is famous for its textiles, watercolours and prints from contemporary and classic artists. You might also see works from Durer, Rembrandt, Hogarth, Turner, Rossetti, Moore, Bacon, and Lowry.

A walk around the gallery through Whitworth Park is entertaining. There are numerous artworks as well as a traditional bronze of Edward VII from 1913 by John Cassidy, the Irish-born Manchester sculptor, more famous for the Colston statue in Bristol that went for a swim. The former director Maria Balshaw, now at the Tate in London, wanted the 2015 refurbishment of The Whitworth to talk to the park outside, and be almost transparent. The most notable successes with that notion are the café which seems to hang among the trees and a new park-facing entrance to the rear. This entrance lies under Nathan Coly’s neon work which spells out the words ‘The Gathering of Strangers’. Among the trees close to the café is Anya Gallaccio’s surprising and moving steel tree, reflecting light, ephemeral, yet a real presence.

In this building in 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst created the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in pursuit of votes for women. There is a small museum on site. Pankhurst was disappointed with the Labour Party, of which she was a member, for not making women’s suffrage a main policy. She was also frustrated by the lack of progress in Parliament in granting women the vote. The WSPU was a militant organisation and their first action was in October 1905 at a Liberal Party meeting in Manchester which resulted in two women, Emmeline’s daughter Christabel and Annie Kenny being arrested which got them in the news. As Emmeline would later articulate. “You have two babies very hungry and wanting to be fed. One baby is a patient baby, and waits indefinitely until its mother is ready to feed it. The other baby is an impatient baby and cries lustily, screams and kicks and makes everybody unpleasant until it is fed. Well, we know perfectly well which baby is attended to first. That is the whole history of politics. You have to make more noise than anybody else, you have to make yourself more obtrusive than anybody else, you have to fill all the papers more than anybody else, in fact you have to be there all the time and see that they do not snow you under.” The WSPU was nicknamed by the Daily Mail, the Suffragettes, as an insult. The women adopted the insult as a badge of honour and changed the pronunciation of the ‘g’ in the word from soft to hard, as they were going ‘get’ the vote, which was achieved in 1918.

Built in 1871, this Roman Catholic church is the dominant religious presence on Oxford Road. It is the most important work by Joseph Aloysius Hansom, a versatile man who also invented the two-wheeled Hansom Cab. The building is impressive in scale especially when viewed from the rear where flying buttresses proliferate. The original design was to have had a 73m (240ft) spire but Hansom died so the tower was finished off by Adrian Gilbert Scott in 1928 with huge Gothic arches.

The interior of Holy Name is simply breathtaking. Designed for a Jesuit community it is light, spacious and seems to almost glow. The church is rib vaulted with terracotta and also faced with terracotta. The lightness in weight of the terracotta explains the extremely thin piers holding up the roof. Much of the decoration and detail was the work of Hansom’s son, Joseph, with his masterpiece here, the High Altar, a feast of architectural detail. In the ‘50s Bing Crosby joined the choir while playing Manchester. In 1985 Morrissey of Manchester band The Smiths, name-checked the church in the song Vicar in a Tutu.

This is an excellent example of the work the University of Manchester has done in creating a more attractive and green landscape around their buildings. On the Schuster Building is a striking mosaic by Hans Tisdall from 1967. This is titled ‘The Alchemist’s Elements’ and while Tisdall didn’t create gold out of base metals he did create astonishingly vivid colours out of glass. The work is so much of its time you feel like sitting down on the nearby benches and playing The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

This attractive terrace of seven, three-bay, two-storey houses probably dates from the 1830s and is now part of the University of Manchester. They tell a story of how the first development of this area of Manchester looked before academia and medical care took over. The district was arranged as a mix of handsome terraces in a grid pattern plus huge properties of rich merchants with generous grounds within reach of city centre offices, warehouses and factories. One of those former houses, again part of the University, sits on the western side of Oxford Road near CityLabs. It’s a short walk to University Green where we began this tour.

University Green and the Arthur Lewis Building

University Green is a relatively new green space. It is part of a landscaping scheme undertaken by the universities in Manchester with the ambition to make themselves as attractive as possible. Along its north side, there are a range of shops and bars underneath the Alliance Manchester Business School. This has a complex history but is now considered one of the most prestigious of European business schools. Academic management trading goes back to 1918 in Manchester and the old Municipal School of Technology we encountered on Walk One of this series. The Business School is named after a prominent sponsor, the Iranian-born, Mancunian-raised industrialist and philanthropist Lord David Alliance. On the other side of University Green is the Arthur Lewis Building. Lewis (1915-1991) was the first black Nobel Prize winner in an academic category, in his case, for economics. He partly developed his ‘Lewis Model’ in Manchester which describes how development was an isolated exercise but one in which political, social and cultural influences were crucial.

Bridgeford Street

A plaque on the wall of the building here declares this to be the building where Professor Williams and Kilburn in 1948 developed the first computer with an electronically stored programme. They called this, aptly, ‘Baby’ and there is a replica in the Science and Industry Museum, Manchester. In Freddie Williams’ words: “A programme was laboriously inserted and the start switch pressed. Immediately the spots on the display tube entered a mad dance. In early trials it was a dance of death leading to no useful result, and what was even worse, without yielding any clue as to what was wrong. But one day it stopped, and there, shining brightly in the expected place, was the expected answer. It was a moment to remember. This was in June 1948, and nothing was ever the same again.”

Manchester Museum

This is a charming building full of picturesque views across halls and stairways, complete with internal bridges and quirky nooks and crannies housing one of the great provincial museum collections. The oldest elements are by Manchester Town Hall architect, Alfred Waterhouse, from 1888. It was extended by his son Paul in 1912 and 1927 and has undergone extensive refurbishment on several occasions.

Waterhouse was asked to produce a building in line with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, with a progression of galleries. Waterhouse in his Natural History Museum in London, opened in 1881, had been asked to produce a building in line with Richard Owen’s Creationist ideas. Architects need to be flexible to gain commissions.

Manchester Museum is particularly strong in natural sciences, geology and botany, including a vivarium with live beasts and archaeology including a well-known section on Ancient Egypt. The latest refurbishment includes a South Asian gallery.

Coupland Street – Physics Laboratory

This redbrick building once hosted one of the best ‘boy bands’ of physicists the world has ever known. Or maybe that should be a ‘nuclear family’, a very diverse nuclear family. The leader of the group was New Zealander Sir Ernest Rutherford who had already gained a Nobel prize in physics by the time he arrived in 1907. Others in his group would include Hans Geiger, the German creator of the eponymous radiation counter, Lawrence Bragg, an Australian and winner of the 1915 Nobel Prize for X-ray crystallography, Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian and analytic philosopher and mathematician and the great Niels Bohr, a Dane and the father of quantum physics. Together the team had many breakthroughs. In 1917 Rutherford discovered that he could ‘disintegrate the nuclei of nitrogen atoms by firing particles from a radioactive source which, in turn, resulted in the release of fast protons.’ He had effectively split the atom.

The University of Manchester – Main Quadrangle

A little down from the Museum another archway opens from Oxford Road and leads into the University of Manchester’s Main Quadrangle the oldest part of the University on this site. Before entering under the arch, note in a niche on the left, a statue of John Owens. John Owens died in 1846 and left £96,654 for the founding of a non-denominational university.

Owens College opened in 1851 on Quay Street, a mile north, before it was decided to move to a larger site, this one, in 1869. In 1880 it became the first part of the Victoria University with other colleges in Liverpool and Leeds. By 1903 it became independent as the Victoria University of Manchester. In 2003 it merged with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology to become just the University of Manchester. It has 25 Nobel laureates to its credit.

Once in the quadrangle then straight ahead is the oldest part of the University of Manchester here from 1873/4. The style of all the buildings surrounding the quadrangle is neo-Gothic and most were designed by Alfred Waterhouse who we have encountered before. Many of the buildings, as with the museum, were finished off by his son Paul Waterhouse. The main quadrangle provides a grand space to stare at architecture.

The Whitworth Hall, at the south-eastern end of the complex, is a mighty space with a grand organ and a stunningly good hammer beam ceiling. It is worth a visit. The organ was donated by Enriqueta Rylands, the first woman to be awarded the honour of freedom of the city. She was the philanthropist who provided John Rylands Library on Deansgate which is now managed by the University.

Set back from Oxford Road is Contact, a space which was set up by the University as Manchester’s Young People’s Theatre. The zany exterior is from Short & Associates in the later nineties. The two stacked ranks of chimney ventilators are part of a natural ventilation system. Many other elements play on the notion of theatrical forms with supporting struts shaped like theatrical spears and the main entrance taking the form of a stage curtain. The theatre was extended by Sheppard Robson in 2022 to complement the 1990s work.

CityLabs and former Manchester Royal Infirmary

On the left-hand side, eastern, of Oxford Road is the former Royal Eye Hospital from 1886 in fierce red brick with terracotta panels of Christ healing the blind. This is now CityLabs, a pioneering research centre for health innovation. The next building on the same side has a long façade with pavilions at the entrance. This was built as Manchester Royal Infirmary and dates from 1908 designed by ET Hall. If it looks like it could be in Greenwich then that is because it is in the same Baroque style. Hall also designed the Liberty & Co department store in London.

This is one of the great galleries of Manchester, but where does the name come from?

There are many occasions Sir Joseph Whitworth’s name has been referenced on these Oxford Road Corridor tours. Whitworth (1803-1887) has been called the father of precision engineering: he was a colossus in his field.

One of his inventions helps the most humble of amateur engineers change a plug. It was Whitworth who came up with the universal screw gauge with the result that people can fix each other’s machines, or change any plug anywhere, without applying back to the original manufacturer of the machine or plug for supplies of their particular screw gauge.

Whitworth was also incredibly philanthropic and it was his legacy funds that provided for the Whitworth Art Gallery, Whitworth Hall and public land on Whitworth Street, see Walk One of this series. The gallery was founded in 1885 but the main, rather heavy façade dates from 1908 by JW Beaumont. The second phase lies inside and is from 1963-8. It is a light and airy design from Bikerdike which is a joy and a triumph of the period. This was enhanced and extended in 2015 by MUMA architects and is another success. The collection is famous for its textiles, watercolours and prints from contemporary and classic artists. You might also see works from Durer, Rembrandt, Hogarth, Turner, Rossetti, Moore, Bacon, and Lowry.

A walk around the gallery through Whitworth Park is entertaining. There are numerous artworks as well as a traditional bronze of Edward VII from 1913 by John Cassidy, the Irish-born Manchester sculptor, more famous for the Colston statue in Bristol that went for a swim. The former director Maria Balshaw, now at the Tate in London, wanted the 2015 refurbishment of The Whitworth to talk to the park outside, and be almost transparent. The most notable successes with that notion are the café which seems to hang among the trees and a new park-facing entrance to the rear. This entrance lies under Nathan Coly’s neon work which spells out the words ‘The Gathering of Strangers’. Among the trees close to the café is Anya Gallaccio’s surprising and moving steel tree, reflecting light, ephemeral, yet a real presence.

University of Manchester NHS Foundation Trust & The Pankhurst Centre

In this building in 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst created the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in pursuit of votes for women. There is a small museum on site. Pankhurst was disappointed with the Labour Party, of which she was a member, for not making women’s suffrage a main policy. She was also frustrated by the lack of progress in Parliament in granting women the vote. The WSPU was a militant organisation and their first action was in October 1905 at a Liberal Party meeting in Manchester which resulted in two women, Emmeline’s daughter Christabel and Annie Kenny being arrested which got them in the news. As Emmeline would later articulate. “You have two babies very hungry and wanting to be fed. One baby is a patient baby, and waits indefinitely until its mother is ready to feed it. The other baby is an impatient baby and cries lustily, screams and kicks and makes everybody unpleasant until it is fed. Well, we know perfectly well which baby is attended to first. That is the whole history of politics. You have to make more noise than anybody else, you have to make yourself more obtrusive than anybody else, you have to fill all the papers more than anybody else, in fact, you have to be there all the time and see that they do not snow you under.” The WSPU was nicknamed by the Daily Mail, the Suffragettes, as an insult. The women adopted the insult as a badge of honour and changed the pronunciation of the ‘g’ in the word from soft to hard, as they were going ‘get’ the vote, which was achieved in 1918.

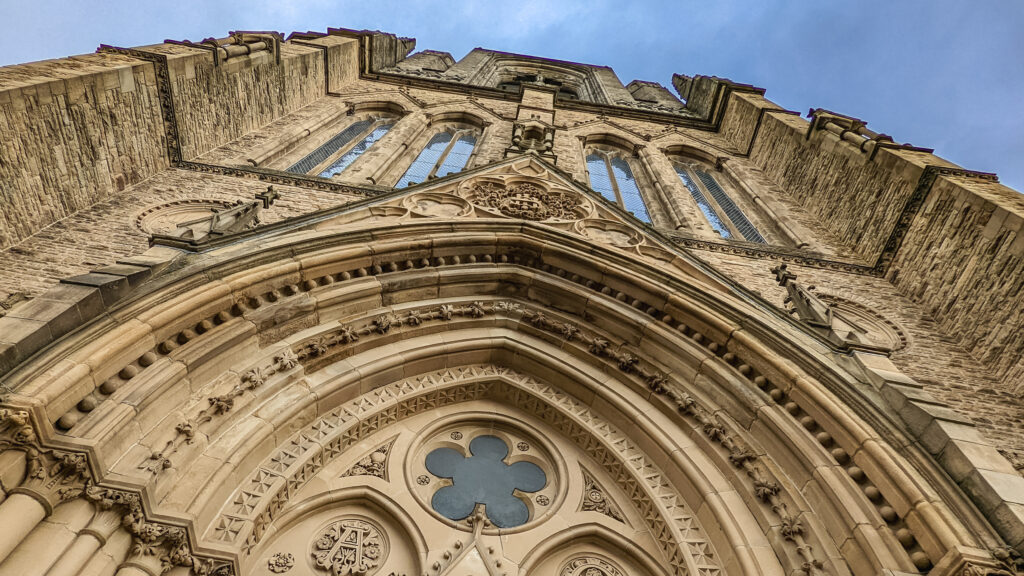

Built in 1871, this Roman Catholic church is the dominant religious presence on Oxford Road. It is the most important work by Joseph Aloysius Hansom, a versatile man who also invented the two-wheeled Hansom Cab. The building is impressive in scale especially when viewed from the rear where flying buttresses proliferate. The original design was to have had a 73m (240ft) spire but Hansom died so the tower was finished off by Adrian Gilbert Scott in 1928 with huge Gothic arches.

The interior of Holy Name is simply breathtaking. Designed for a Jesuit community it is light, spacious and seems to almost glow. The church is rib vaulted with terracotta and also faced with terracotta. The lightness in weight of the terracotta explains the extremely thin piers holding up the roof. Much of the decoration and detail was the work of Hansom’s son, Joseph, with his masterpiece here, the High Altar, a feast of architectural detail. In the ‘50s Bing Crosby joined the choir while playing Manchester. In 1985 Morrissey of Manchester band The Smiths, name-checked the church in the song Vicar in a Tutu.

This is an excellent example of the work the University of Manchester has done in creating a more attractive and green landscape around their buildings. On the Schuster Building is a striking mosaic by Hans Tisdall from 1967. This is titled ‘The Alchemist’s Elements’ and while Tisdall didn’t create gold out of base metals he did create astonishingly vivid colours out of glass. The work is so much of its time you feel like sitting down on the nearby benches and playing The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Waterloo Place

This attractive terrace of seven, three-bay, two-storey houses probably dates from the 1830s and is now part of the University of Manchester. They tell a story of how the first development of this area of Manchester looked before academia and medical care took over. The district was arranged as a mix of handsome terraces in a grid pattern plus huge properties of rich merchants with generous grounds within reach of city centre offices, warehouses and factories. One of those former houses, again part of the University, sits on the western side of Oxford Road near CityLabs. It’s a short walk to University Green where we began this tour.

Some of the best Galleries & Museums in Manchester are here on Oxford Road Corridor. Explore a diverse programme for all cultural enthusiasts.

Oxford Road Corridor has a number of historic parks and contemporary green spaces to enjoy.

The food and drink in Manchester is some of the best in the UK with many of the finest offerings found here on the Oxford Road Corridor.