Manchester is leading the 2D revolution and home to the UK’s leading research and innovation association of advanced materials.

Jonathan Schofield explores the fascinating shared history of Manchester Metropolitan University and the University of Manchester.

Manchester’s commercial muscle started to flex in the second half of the eighteenth century and went full bodybuilder as the nineteenth century progressed. The region was ripe with ideas and numerous individuals wanted in.

The energy at the time was remarkable with an insatiable thirst for new technical processes, new machines, new solutions. Much of this was driven by a desire to make money with little thought to the social consequences further down the economic ladder.

But the mercenary impulse was not the only one.

There were far loftier ambitions from the start; first in driving forward science, medicine and pure knowledge and then in addressing the city’s social problems. People knew education and training was key to this. They also knew working together was vital.

A quote from those late eighteenth-century days sums up the mood. In 1785 a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (MLPS) wrote: ‘Men, however great their learning often become indolent and unambitious to improve in knowledge for want of associating with others of similar talents and improvements. But science, like fire, is put in motion by collision. Where a number of such men have frequent opportunities of meeting and conversing together, thought begets thought, and every hint is turned to advantage. A spirit of enquiry glows in every breast.’

Replace ‘men’ with ‘people’ and the quote is as relevant today, particularly for institutions of learning such as the University of Manchester (UoM) and Manchester Metropolitan University (Manchester Met).

A founding member of MLPS was the physician Thomas Percival. He was the society’s president from 1782 to 1804 and was the first person to use the phrase ‘medical ethics’ in a series of pamphlets which still form the basis of the modern approach to the field.

The study of medicine was a high priority given the mortality rates of the time. The human body had to be understood and so Joseph Jordan set up a School of Anatomy in Manchester in 1814, the first in the English provinces. Anatomy needed corpses and Jordan got them by any means he could. On one occasion he was fined but while his ‘resurrectionist’ was gaoled Jordan was released as the magistrate understood the need for students of surgery to learn their trade. Jordan was a curious man and kept human bones under his bed.

Thomas Percival was the father of Ann Percival who was the mother of Benjamin Heywood, banker and philanthropist who created and was the first president of The Mechanics’ Institute from its creation in 1824. This is considered Year One of today’s mighty institutions of UoM and Manchester Met despite their complicated family trees.

At a meeting in the Bridgewater Arms on 17 April 1824 it was resolved, in a somewhat patronising manner, that: ‘The object of the institute is to instruct the working classes in the principles of arts they practice and in other branches of useful knowledge, excluding party politics and controversial theology.’

Manchester was already by then the most political of UK cities so maybe the meeting members might not have been too surprised about the debates that rage in the Institute’s 21st century descendants.

The founders included a roll call of Mancunian pioneers. Two examples will suffice. William Fairbairn was a giant of engineering developing new textile machines, perfecting boilers and even building bridges and ships. Joseph Brotherton was a cotton baron who was the first MP for Salford from 1832, an abolitionist, a promoter of national secular education, a campaigner against the death penalty and a prime mover behind the creation of the Vegetarian Society in 1847.

The foundation of the Institute took place seventeen years after the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire but still nine years before an act of Parliament banned the holding and working of slaves within the colonies. It has to be acknowledged some founders had links to slavery including the prime mover, Benjamin Heywood. He was an abolitionist but earlier generations of his family, in Liverpool, had owned slave ships. The origin of his wealth owed much to slavery.

The second building of the Mechanics’ Institute opened in 1856 designed by John Gregan in Manchester’s Italianate ‘palazzo’ style. It still stands on Princess Street. It was here in 1868 where the Trades Union Congress was founded. It was also here in 1851 that Caroline Dexter lectured on ‘Bloomerism’: a movement dedicated to making it permissible for women to wear trousers.

The Mechanic’s Institute morphed into the Manchester Technical School in 1880 by which time Britain’s industrial hegemony was being challenged by Germany, France and the USA which were developing better educational and training systems.

Stepping back in time a little, in 1838 the Manchester School of Design had opened. A notable person involved with this was another great engineer and philanthropist from Manchester, Joseph Whitworth. Whitworth’s name is stamped across the city with Whitworth Street and UoM’s Whitworth Art Gallery and Whitworth Hall. He came from a relatively lowly background and was always interested in design and technical education.

Bear with me here. The Manchester School of Design became the Manchester School of Art of 1853 which linked with another Joseph Whitworth school, The Whitworth Institute, which was tied inextricably to the Manchester Technical School. Thus, a common ancestry is reached with the Mechanics’ Institute.

One notable arrival to the School of Art in 1907 was Adolphe Valette. A Frenchman from St Etienne he’d arrived in the city as a designer for a Manchester printing firm. He attended evening classes at the School of Art and was so good he was invited to teach there. Valette was affectionately known as ‘Monsieur Repent’ by students, a play on his accent and his frequent request to ‘repaint’.

Valette eschewed the notion of painting bucolic rural scenes and instead captured industrial Manchester at its peak particularly the chemical soup of its atmosphere. In Valette’s vision, the physical world is dissolved in water and light, edges soften and colours merge. Beauty is distilled from seemingly brutal industrialisation and pollution. A disciple of Valette’s was Laurence Stephen Lowry and the influence on the ‘matchstick men’ artist is obvious.

Years later Ossie Clark would become an alumnus who helped create the swinging sixties with his flamboyant fashion designs. The portrait of Clark and his wife, Celia Birtwell, by David Hockney, is one of the defining images of the period. Fashion design has been a huge part of the Manchester Met story and remains so. Former student Sarah Burton has been the creative designer for the Alexander McQueen fashion house and designed Kate Middleton’s wedding dress when Middleton married Prince William in 2011.

The School of Art became Manchester Polytechnic in 1970 and would play its part in the resurgence of the Manchester punk and indie explosion and again helped create a template for the times. Both Malcolm Garrett and Peter Saville were students along with Mick Hucknall of the band

Simply Red.

Garrett designed for several Greater Manchester bands such as The Buzzcocks and later with other groups such as Duran Duran. He was one of the first people to see the opportunities available through digital technology. Saville was the in-house designer for Factory Records and his work for bands such as Joy Division and New Order, amongst others, has become legendary. The present institution of Manchester Met was created in 1992 out of Manchester Polytechnic. The growth of the university seems to show no signs of slowing.

The fact Carol Ann Duffy, the professor of contemporary poetry at Manchester Met, was Poet Laureate between 2009 and 2019 underscores why Manchester Met hosts the Manchester Poetry Library in a recent building, Grosvenor East for the Arts and Humanities faculty. In the last decade or so additions to the estate have included the award-winning Business School, the School of Art’s splendid Benzie Building, the Brooks Building for Health and Education, the pioneering School of Digital Arts and most recently the Institute of Sport.

The Manchester Met estate is fascinating for other historical connections too. The façade of the former Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall forms part of the Arts and Humanities faculty. It was in the then Town Hall where in October 1945, the fifth Pan-African Congress met. As delegate Jomo Kenyatta said: ‘This was a landmark in the…struggle for unity and freedom (in Africa)’.

Time to roll back time again. As we’ve seen Manchester School of Art of 1853 had links with Whitworth Institute from 1891 which then joins with the Manchester Technical School.

It was the legacy of our dear Mr Joseph Whitworth once more which provided funds, through his trustees, to help deliver the splendid buildings (from 1895) on Sackville Street for what was by that time the Municipal School of Technology. The Godlee Observatory that gloriously crowns these buildings was the gift of Francis Godlee, a man we’d now call an early adopter. His telephone number was four. Just four.

Sixty years later, over the railway viaduct from the School of Technology would rise one of the most distinctive university city campuses in the UK with the modernist buildings of what would be the University of Manchester, Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST). This was given its charter in 1968 and is a direct descendant of the Mechanic’s Institute of 1824.

When UMIST merged with the Victoria University of Manchester in 2004 the University of Manchester was born and the link with the Mechanics’ Institute cemented.

Part of that complex family tree had come from a different seed.

John Owens, textile manufacturer and merchant, loner, bachelor, frequently unhealthy and miser, became the unlikely creator of a key element of one of the great European universities. He left in 1846 £94,654 (£16.5m in 2024) to create a non-denominational college (one without religious barriers). The strange little man is commemorated by a statue standing high in its niche close to the main Oxford Road entrance of UoM.

In truth, it was the affable friend of Owens, George Faulkner, who was the real force behind the institution and probably his suggestion in the first place. It was principally his energy which led to the college opening in 1851 and he was the first chair of the trustees until 1858 supplementing the college’s revenues with his own money.

The home of the original Owens College stands on Quay Street, an adapted townhouse from the 1770s that had been the home of Free Trade politician and radical MP Richard Cobden for fourteen years from 1836 to 1850.

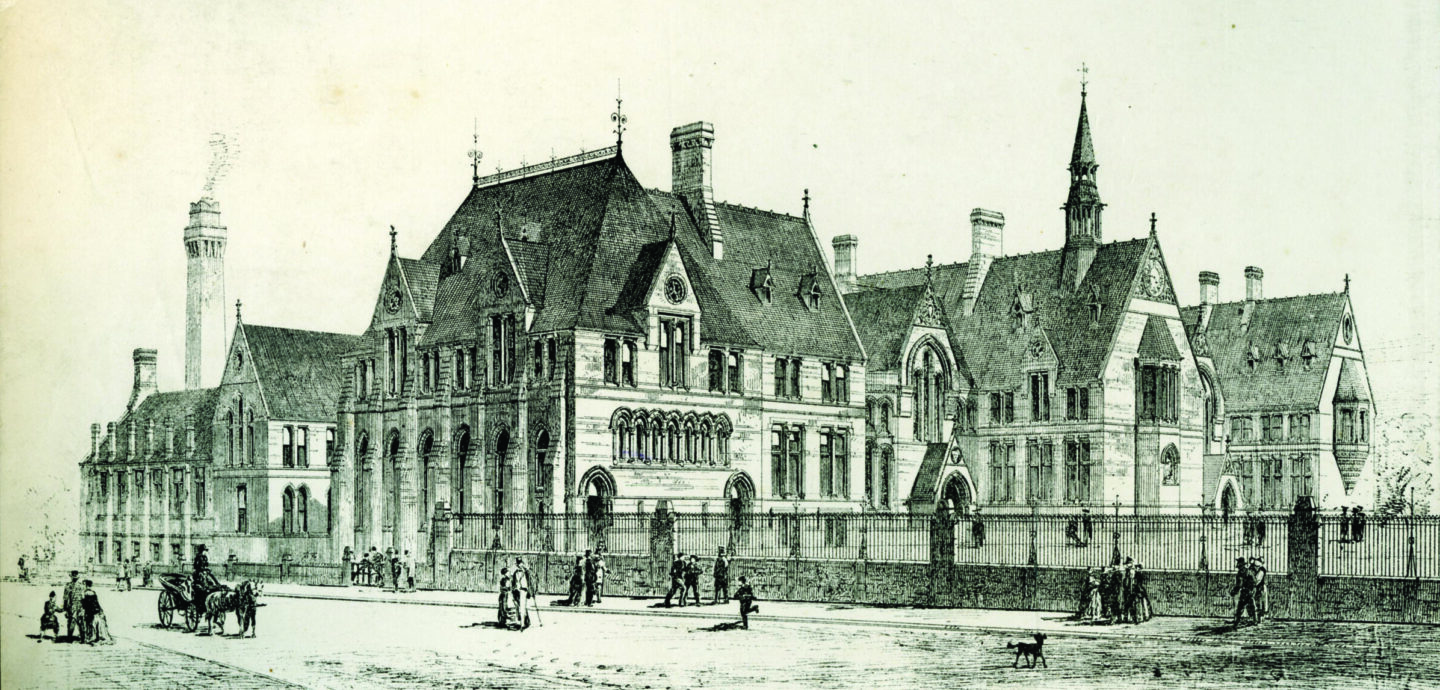

The success of the college meant the former house was never going to be large enough so in 1869 the celebrated architect Alfred Waterhouse was commissioned to build (and build grandly) in the neo-Gothic style along suburban Oxford Road. Waterhouse had not long won the competition design for Manchester Town Hall which followed from the success of his Manchester Assize Courts.

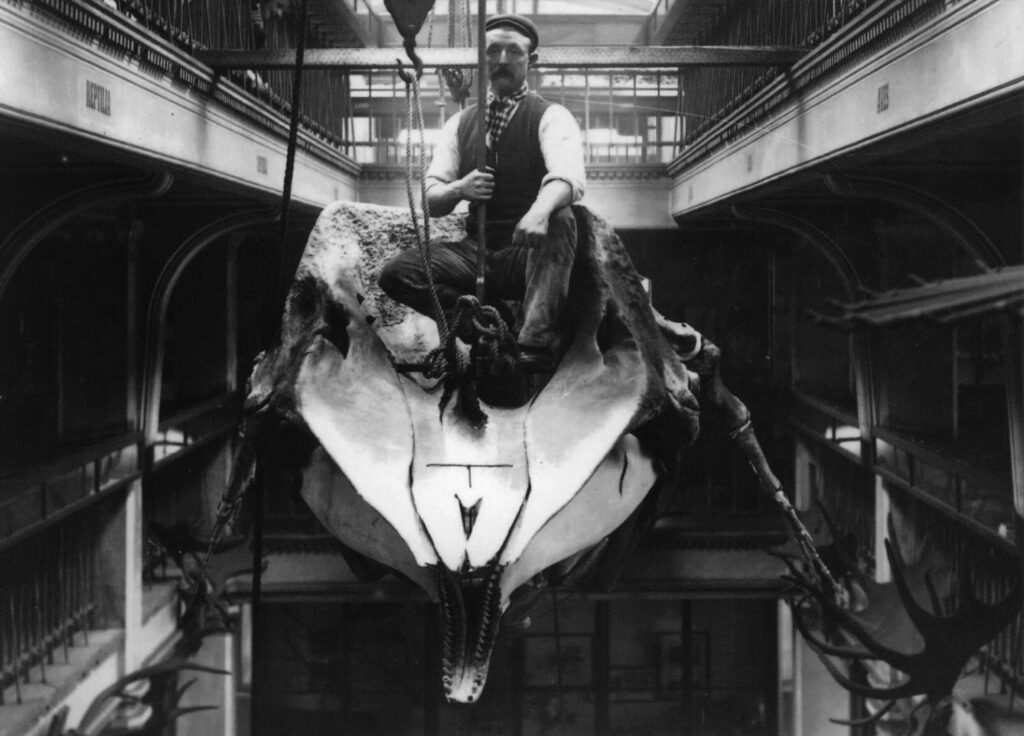

Waterhouse’s work is stamped firmly all over these older UoM buildings. In 1888 his Manchester Museum opened, following the opening of London’s Natural History Museum also to his designs. Most of the other buildings here were designed by Alfred or his son Paul. Manchester is unusual with its museums. Take any major European cultural centre and the main museum will be owned and operated by the municipality. In Manchester UoM owns and operates Manchester Museum, plus one of the main art galleries, the Whitworth Art Gallery, as well as the main research library, the incomparable John Rylands Library.

Owens College incorporated the Royal Manchester School of Medicine in 1872 and thus the square was circled with Thomas Percival and Joseph Jordan. In 1880 Owens College became the first college of the Victoria University with Liverpool joining in 1884 and Leeds in 1887. Manchester broke free of its fellow northern cities in 1903 and became the Victoria University of Manchester. The merger with UMIST created the entirely sensible moniker of the University of Manchester.

There are many stories.

Down the years there has been astonishing success for the University but let’s start with a scandal eh? George Gissing, before he became the acclaimed novelist of New Grub Street, gained a scholarship to Owens College but was caught red-handed stealing from the college cloakroom in May 1876. He was convicted of theft and sentenced to a month’s imprisonment. He’d wanted the money to ‘reclaim’ a young prostitute, ‘Nell’ Harrison, with whom he’d fallen in love. The shame he felt was apparent in many of his subsequent works.

That is just one dramatic incident in university life, there’s simply too much material to discuss in length here how the university grew in both scale and significance, although perhaps a few instances might be mentioned.

In the early years of the twentieth century, Manchester gathered together one of the best boy bands of scientists in history. Ernest Rutherford, a New Zealander, was persuaded into coming to Manchester in 1907. He was already well-known for winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in Canada.

He took up the position of Chair of Physics at the University and became the centre of an extraordinary ‘nuclear family’. As with today’s educational institutions along Oxford Road, it was a multi-national group. There was Hans Geiger from Germany, of Geiger Counter fame, Australian-born Lawrence Bragg, who would win the 1915 Nobel Prize for his work on X-ray crystallography; Ludwig Wittgenstein from Austria, the analytic philosopher; and Niels Bohr from Denmark, the father of quantum physics. The group would make a series of world-changing discoveries, particularly with regard to atoms.

Rutherford’s laboratory was on Coupland Street, behind Manchester Museum, next door again was a modest building housing the electricity boffins. Alan Turing, famous for his work at Bletchley Park, worked here post-WWII and developed his ‘Turing Test’ or, in his words, the ‘Imitation Game’. This remains the test for artificial intelligence and, of course, it’s never been more relevant.

In the same building at the same time Professors Kilburn and Williams were developing Baby, said to be the first computer with an electronic memory. Freddie Williams subsequently came up with one of the most stirring of scientific quotes.

“A program was laboriously inserted and the start switch pressed. Immediately the spots on the display tube entered a mad dance. In early trials it was a dance of death leading to no useful result, and what was even worse, without yielding any clue as to what was wrong. But one day it stopped, and there, shining brightly in the expected place, was the expected answer. It was a moment to remember. This was in June 1948, and nothing was ever the same again.”

A brand new building on the campus is named for Christabel Pankhurst, daughter of the Suffragette pioneer Emmeline Pankhurst, and just as fierce a campaigner. The family home was a short distance away on Nelson Street. It still survives overshadowed by buildings of the Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

Christabel gained a law degree with honours but was not allowed to practice. In a passionate speech in 1904 in Manchester’s Athenaeum she rebuked the males in the room and pointed out how women must be allowed to practice so they can earn a living, be independent and further, ‘have the right to consult and take advice from women.’

So many stories, so much achievement leading to the University being associated with 25 Nobel Prize winners.

So many mighty buildings too. Let’s take 2022’s spectacular MEC-D, the engineering campus. This is the size of 16 football fields and has a high-voltage room which can generate enough energy to power up a town of 100,000.

Indeed, is there anywhere like Oxford Street/Oxford Road leading to Wilmslow Road in the UK?

The name of the road might vary for historical reasons, but this doesn’t change the fact this is definitely one road and perhaps the most representative in the country. Travel from Fletcher Moss Gardens in Didsbury through Withington, Fallowfield and Rusholme to Whitworth Park, past the vast hospital complex and into the bustling university campuses, and you travel from quiet leafy suburbs to ivory towers via multi-cultural vibrancy and parks. It’s all urban Britain on one road.

For the two great academic institutions of the UoM and Manchester Met it’s been less direct, a long and winding road. Those founders of the Mechanics’ Institute would no doubt be proud of their legacy. From little acorns grow mighty oaks: that two such mighty oaks as UoM and Manchester Met have taken root and flourished is testament to a continuous pursuit of educational ambition and educational entrepreneurship in the city.

Two hundred years on the achievements of alumni are written in Nobel prizes across the world and with numerous pioneers in all walks of life from the sciences through the humanities and into culture and politics.

The Mechanics Institute’s resolution about tuition and study in ‘other branches of useful knowledge’ has spread wide indeed.

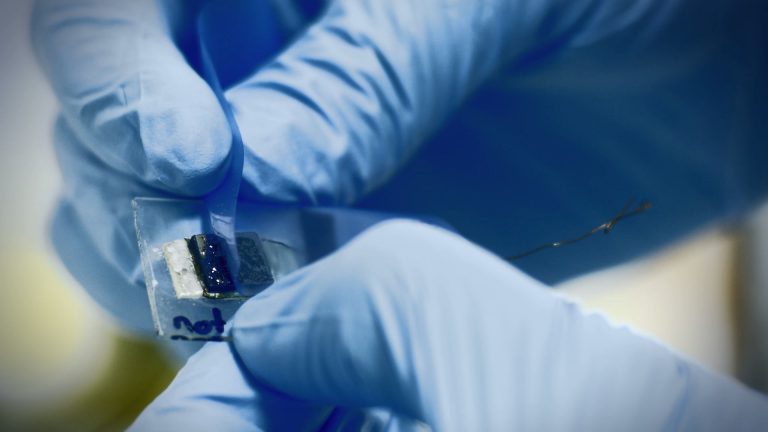

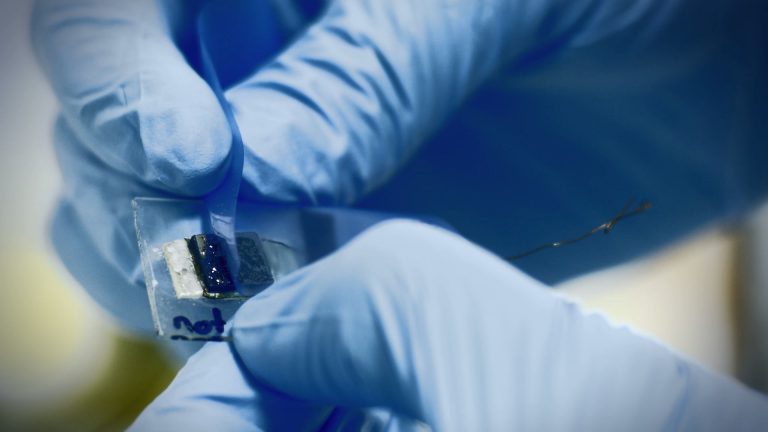

Manchester is leading the 2D revolution and home to the UK’s leading research and innovation association of advanced materials.

Oxford Road Corridor is home to one of the largest clinical academic campuses in Europe, attracting clinicians, students and researchers from around the world.

The availability of digital talent generated by the two universities on the Oxford Road Corridor is a major factor in the city region’s success in attracting inward investment and growing new digital firms.